I remember

2008 mainly for two things: the somewhat quirky apartment I was living in at

the time and a new gaming craze that seemed to be taking over gaming space

everywhere any was available. The craze was called Dominion, and it was spreading like a surprisingly fun virus with the sickness heralded not by sticky coughing and thunderous sneezing,

but by silent rustle of a shuffled deck of cards.

|

| Image source: BoardGameGeek |

I did not

stick with the strange apartment, but the base set of Dominion is still on my gaming shelf. The worn out money cards

remind me of literally hundreds of games played and all the people around me

that had fun with the game. Donald X. Vaccarino’s ingenious child left an

impression on many gamers, grew with new expansions and, probably even more

importantly, created a new genre of games, with many designers jumping on the

opportunity to use this new and hip thing called deckbuilding.

The gaming

world needed to wait less than a year to see other deck builders emerge, with AEG’s

Thunderstone arriving with probably

the biggest splash. The fantasy dungeon romp brought what many people missed in

its predecessor: a stronger theme, a flavour and a slightly lower level of dissociation

of game mechanisms with what they were supposed to represent; but it also lost some of Dominion's smoothness in the process. Now,

six years after Dominion first

conquered the gaming market, dozens of deckbuilders inhabit our gaming shelves

and it is clear that the genre spawned by Vaccarino’s creation is here to stay –

and evolve.

|

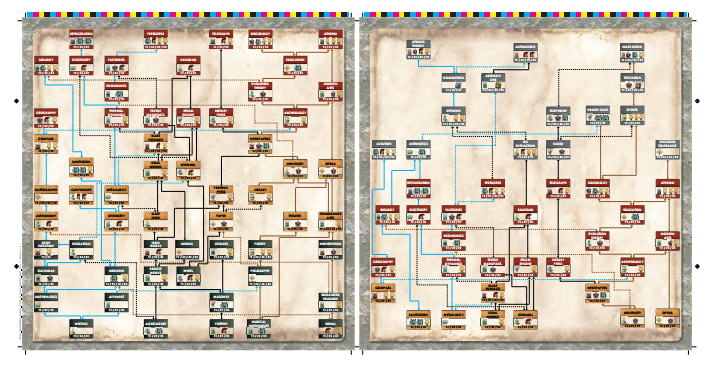

| Image source: BoardGameGeek |

Thematically

wise, Dominion, Thunderstone and many others offered no explanation as to why the

mechanism is there – nor did they need one, as building decks, shuffling and

playing cards was so much fun, nobody would ask what the system is supposed to

simulate. Over time however, designers started to either associate deckbuilding

with a specific phenomenon it was supposed to depict in their games, or use it

as only one of the elements of gameplay, re-implementing, re-mixing and

crossing new boundaries to use all deckbuilding has to offer, succeeding or

failing in the process.

|

| Image source: BoardGameGeek |

A great

example of the above is the tragically flawed A Few Acres of Snow by Martin Wallace – a game, where the growing

deck simulated the difficulties a French or English leader had to face while

waging war and colonizing at the same time, having to whip their growing,

unruly empire of towns and traders into battle-ready submission. The game

succeeded almost flawlessly in employing deckbuilding as an abstraction of a

specific process – and failed utterly in balancing the two sides of conflict,

making it a broken, but nonetheless beautiful thing.

|

| Image source: BoardGameGeek |

Finally, we

also have games that use deck building as just another element of the puzzle,

which do not revolve solely around building a strong deck and make players

focus on things other than what next will they buy and discard. Vlaada Chvatil’s

Mage Knight serves a great example of

how the mechanism can be both prevalent and yet not the centrepiece of an engaging,

deeply thematic game. Ryan Laukat’s Cityof Iron proves that deckbuilding has its place in more traditional German

style games. Mac Gerdts’ excellent Concordiawalks away from deckbuilding, becoming a fascinating exercise in area control

and managing a deck-sized hand of cards.

With its popularity

and incredible potential, deck building is something all “people of gaming” should

keep an eye on, as there are still opportunities of putting it work in new and

interesting ways – or to build upon the simple idea that became a great game, a

craze, a genre and finally, a new cornerstone for the games to come.

__________________

Follow us on Twitter: @NSKNGames